This is a guest blog written by an experienced foster carer. The blog contains references to domestic abuse.

We had just said goodbye to our first fostered child when the call came from the “finding a Home” team.

They were expecting a baby to be born within the next few days and were asking if I would be ready to give that little one a home while decisions were being made about their future.

Three days later, on a mild October morning, while I was at the hairdressers, the next call came.

Baby Jude* had been born and the Social Workers were bringing him to our house.

I ran home from the hairdressers (thankfully she was only round the corner from our house!) and started to get everything ready to welcome a tiny newborn into our home, but nothing could prepare us for what the next 3 months would hold.

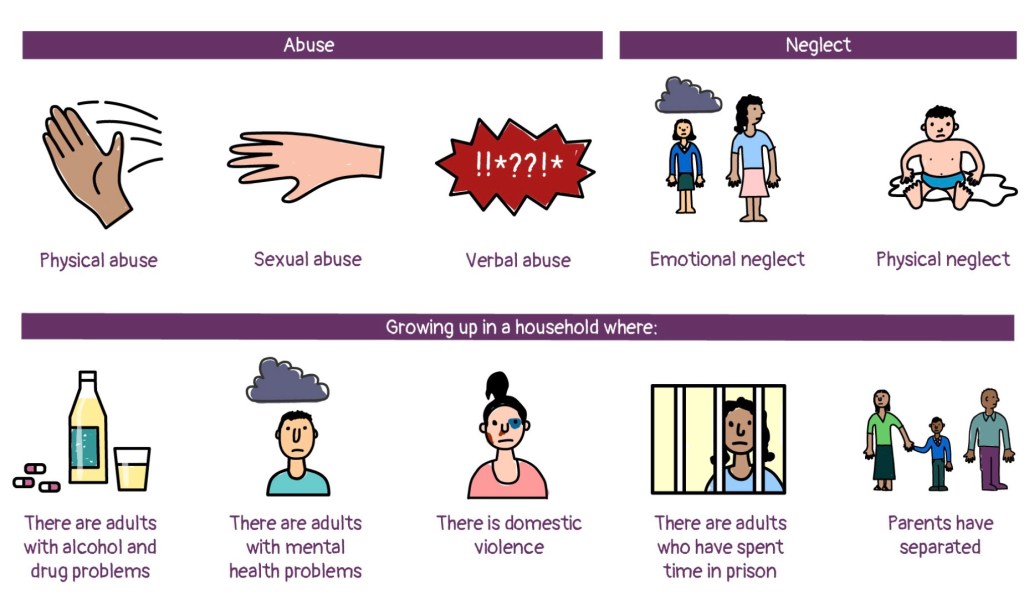

When Jude was born his Dad was awaiting trial for setting fire to the home Jude’s pregnant Mum was in. The domestic abuse had started soon after the relationship began and it didn’t stop whilst she was pregnant.

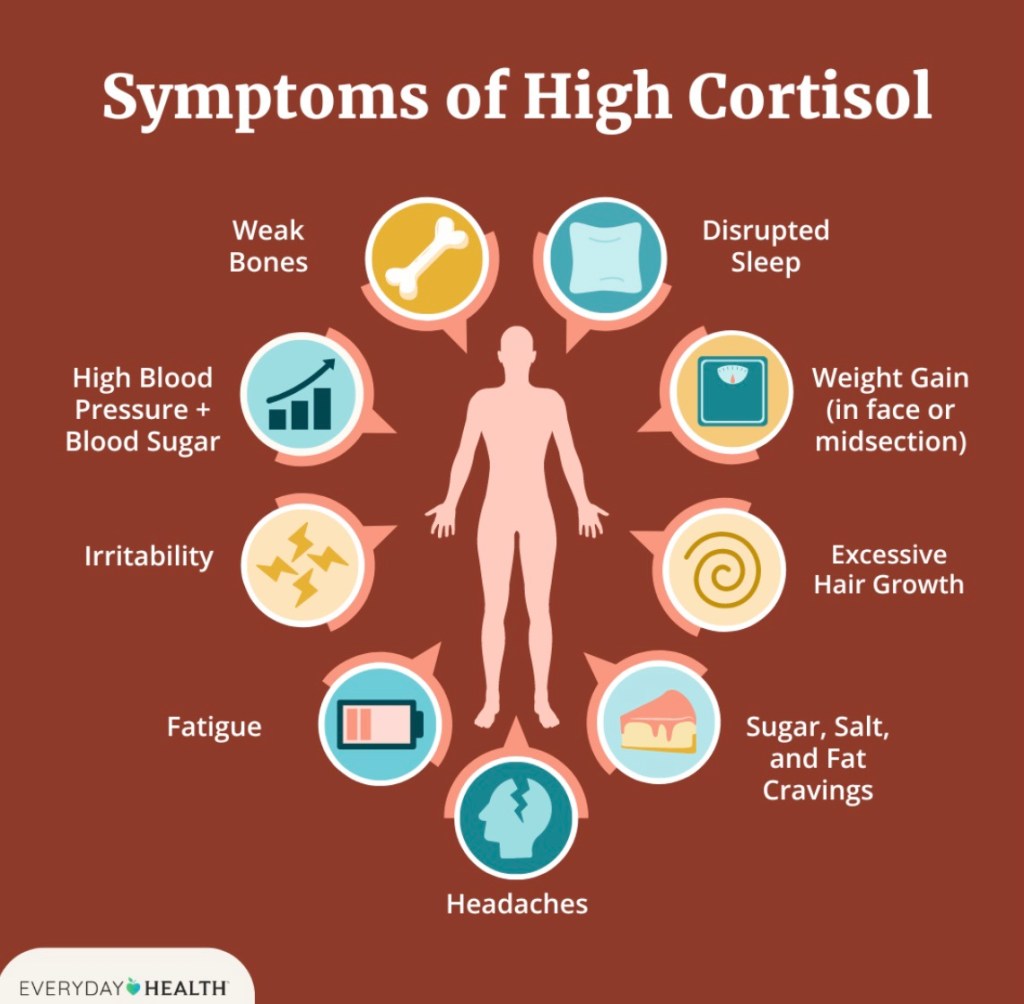

Jude was 5 hours old when he was left in our care, and he was hyper vigilant.

Even at that young age he was constantly assessing potential threats around him.

I lay him on the mat to change his nappy and as I moved towards him to undress him he moved himself away from me, he was 1 day old.

He refused to sleep and cried at every sound, every movement.

Cuddling him was nearly (note, “nearly”) impossible, as we picked him up he arched his back making it very hard to hold him close.

We didn’t sleep for 3 months as we stayed awake with him, watching over him, getting as close to him as he would allow and praying for him. It was a herculean effort by the whole fostering family, but, little by little, day by day, he learnt to trust that we weren’t going to hurt him like his Dad did to his Mum before he was even born.

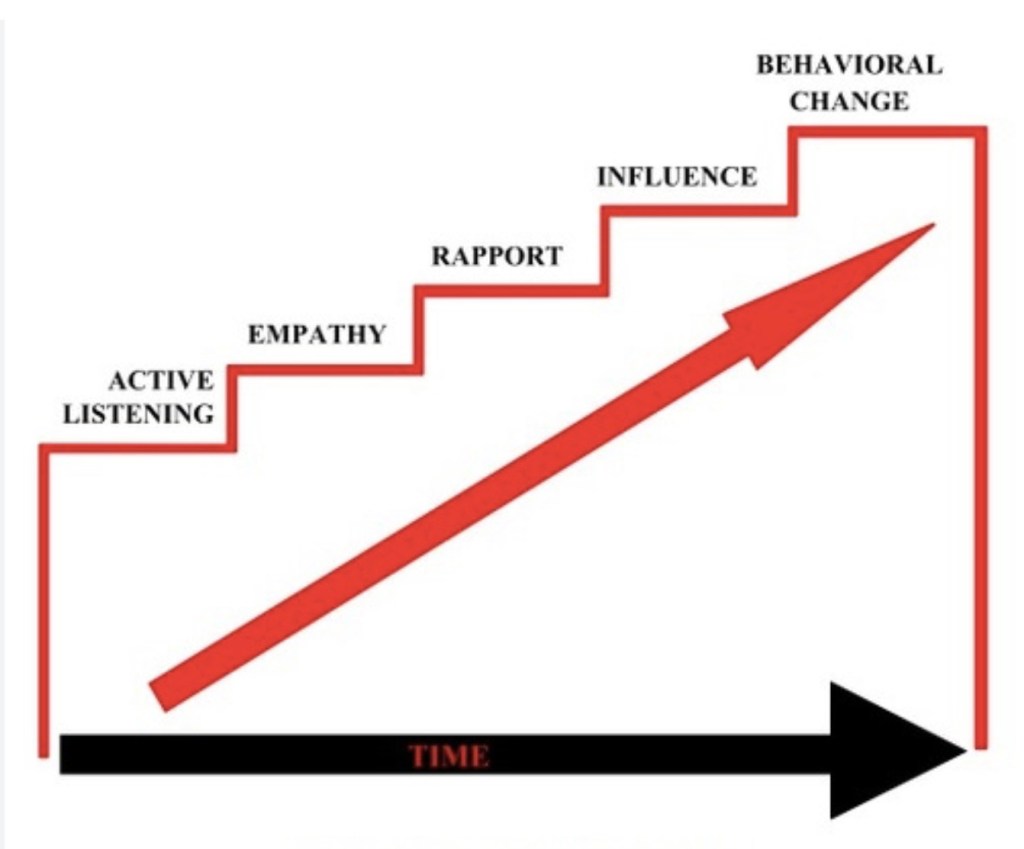

We learnt to go at his pace, not to smoother him and scare him further, but to earn his trust though small steps.

It took 3 months and more for the cortisol levels to come down to a point where he could safely sleep.

At that time very little was known about pre-birth trauma and we had no idea what we were dealing with.

We were flying on instinct and it was tough, as many things we tried just seemed to make things worse!

It wasn’t until years later that we learnt about how trauma, and domestic abuse, can affect babies in the womb, and suddenly everything we had lived made sense.

Jude lived with us for almost 2 years and became a gorgeous, loving, caring, beautiful toddler.

Almost 13 years later we can still see the difficulties he has because of those early, pre-birth, experiences.

In school he makes himself as small, quiet and unnoticeable as possible, he is wary of people who may harm him and any supply teaches are a huge threat to his wellbeing.

When a stranger enters his vicinity the cortisone levels rise again and the same fears rise to the surface.

But, we are still in touch with him, and his beautiful family, and he he knows how special he is to us, and that there are adults who can be trusted.

*Jude is not the child’s name